“History of the Seminoles and Southeastern Tribes, Pre-Contact to Present” is an elective many have chosen because they’re “Seminoles” who wish to know more about real Seminoles than just the Florida State Seminoles, the football team for which they’ll root in a national semifinal against Oregon on New Year’s Day. So the details of Seminole history flow from the captivating voice of Andrew Frank, whose brain never seems to lose its place across 75 minutes.

He tells them it’s hard to look back through the past few centuries and peg when the Seminole Tribe self-identified as Seminoles, but they first centralized as a tribe in 1957. He tells how Seminole ancestors, including the tribe called Creeks, traveled by “dug-out canoe” because, “If you need to go 20 miles, better to float there than walk there.” He’s on his semester-long way toward modern day, when he again will inform students that modern-day Seminoles are adept businesspeople, and that the trappings of mascot-hood can fail miserably at accuracy.

He might even tell them, as he said in an interview, “It’s hard to imagine 4,000 people wielding real political power and economic clout, and they do so gracefully.”

The course — born in 2006, hatched right after the NCAA clamored about changing Native American mascots, conceived with input from the Seminole Tribe of Florida — doubles as epitome. It demonstrates the unusual bond between a 41,000-strong university way up in the Florida Panhandle and a 4,000-strong tribe that history shoved into the Everglades and below Lake Okeechobee and way down almost to Miami, some 400 miles from Room 208 of the HCB Classroom Building. It helps explain why, if Native American mascots keep ebbing in the United States through the 21st century, “Florida State Seminoles” could be the last one standing in the 22nd.

A Florida State Seminoles cheerleader runs with a flag bearing the team’s logo. (Ronald Martinez/Getty Images)

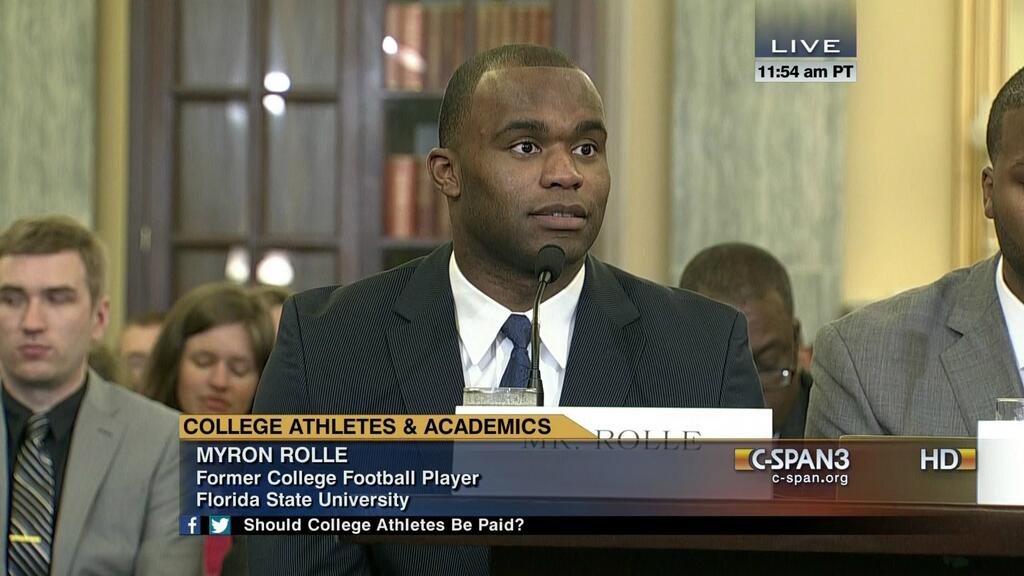

“It’s an absolute reverence,” said Myron Rolle, the 28-year-old former Florida State safety and Rhodes Scholar. “It’s a reverence where the spirit, the unconquered nature of the internal values and ethos of these people, FSU tries to embody that. I love the way it’s intertwined.”

“I just feel a huge amount of honor,” said Justin Motlow, a freshman walk-on wide receiver who just became possibly the first Seminole Tribe member to play football for Florida State.

“I think it was a learning process for both parties,” Louise Gopher, an elder in the Seminole Tribe of Florida, wrote in an e-mail.

“I’m never under-enrolled,” said Frank.

A fascinating culture

At Florida State’s fall commencement on Dec. 13, the keynote speaker and honorary-doctorate recipient was Gopher, the Seminole Tribe of Florida’s first female college graduate (1970, Florida Atlantic). “I don’t think my feet have touched the ground yet on receiving an honorary degree,” she wrote in an e-mail.As Florida State administrators altered the sports teams’ logo and fashion last spring, they consulted the tribe, and new patchwork appeared on jersey sleeves. Tribe leaders who visit Tallahassee know both the president’s yard and the stadium’s cheers.

Two Seminole Native Americans named Heni Yahula, known as Cowdow Billie, and Hia-Et-Tee, known as Annie Tiger kiss after they were married in front of members of their tribe in Miami on March 16, 1930. (AP Photo/Associated Press)

Last Mother’s Day weekend, Frank joined a few Florida State officials on a flight south, where they attended a powwow and a Tribal Council meeting and brought gifts that included women’s basketball uniforms. A flute player/storyteller visits Frank’s classroom every semester for no cost other than hotel and gasoline, and he stops off to stock up on Florida State apparel. Some students from Frank’s classes have gone on to internships with the tribe.

When Rolle sought to use his football stature to start a benevolent project, he consulted then-university president T.K. Wetherell, who suggested Rolle look into the Seminole Tribe. Rolle did so. He learned of obesity, hypertension and Type 2 Diabetes in Native American children, made that his project, spent 100-plus days at the three South Florida Seminole reservations, lectured children about vegetables, became something of a local hero and served as grand marshal in a parade.

Across the Atlantic at Oxford, he wrote his Rhodes medical anthropology thesis about North America. Title: “The Native-American Body: Internal and External Controls.”

“It just fascinates me, this culture,” he said.

Eliminating stereotypes

Rolle also notes that his brother, McKinley, a Florida high school football coach, graduated from St. John’s (N.Y.), which in 1994 changed its nickname from “Redmen” to “Red Storm.” That joined the decades of nickname exodus that have included Dartmouth (“Indians” to “Big Green”), Stanford (“Indians” to “Cardinal”), Miami of Ohio (“Redskins” to “Red Hawks”), Syracuse (“Orangemen” and “Orangewomen” to “Orange”), Utah (“Redskins” to “Utes”). When the University of North Dakota played the men’s ice hockey Frozen Four last spring in Philadelphia, it brought along no nickname.North Dakotan voters overwhelmingly nixed the name “Fighting Sioux” in 2012. A new name will appear in 2015.

The same NCAA that aimed to scrub away the stereotyping granted a waiver to Florida State in 2005. It cited unique circumstances. Those included the partnership that stretches from Tallahassee to the three reservations amid the base of the state: Hollywood, Brighton and Big Cypress. While the Seminole nickname dates back to 1947, the partnership accelerated in 1976, after Bowden arrived to coach and Durham arrived to dine one night at Bowden’s house. The football program had no real national identity. When Durham suggested forging a tradition of a student horseman depicting the revered Chief Osceola (1804-30), with a seasoned student horseman riding out to the field with war paint and a spear, and Bowden agreed, Durham consulted the Tribe straight away. He asked Howard Tommie, the former tribal chairman, who said, “I’ll have ladies here at the reservation make your first regalia for you.”

“And so he did,” Durham said, “and he sent it on a Trailways bus.”

Through time and Seminole input, the university has made tweaks including, Frank noted, the discontinuation of a Sioux headdress for the Homecoming king. “Lots of changes took place outside the public view,” Frank said. “One of the things was there was a booster club, a group on campus that used to be called ‘Scalp Hunters,’ and they were the ones at the football games who would paint your face on the way in. Now they’re ‘Spirit Hunters.’ The name was changed, became remarkably innocuous, and I know there are groups out there that don’t call themselves ‘Spirit Hunters,’ but they’re not the official group on campus anymore. And ‘Spirit Hunters,’ how hard is that?”

Historical oddities do linger. Stadium rituals include fans “war-chanting” and using arms for “tomahawk-chopping.” “We also understand that some of it is for show, such as the horse, Renegade, and the flaming spear, and we are okay with it,” Gopher said. Around town, Native American iconography still appears on some local businesses such as vacuum repair. A restaurant at the edge of campus goes by the name Tomahawk’s, which baffled some scholars visiting Florida State for a conference.

“We sell our MBA program with a tagline,” Frank said, referring to “War Paint for today’s business world,” the MBA Web site headline above a photo of former quarterback and MBA holder Christian Ponder with painted cheeks. “In my head, I don’t need war paint to explain why the Seminoles are good at business,” Frank said. “They run a billion-dollar industry (the Hard Rock Resort & Casino in South Florida). They are one of the most successful cattle-herding companies in the state of Florida. They run their own brand of orange juice. They have bottled water. They have agriculture. They have real estate. They have a remarkably diversified portfolio that allows them to pay their citizens monthly annuity checks. They pay out taxes rather than receive taxes from their citizens. It’s a pretty remarkable model of an efficient, well-run corporation that’s always looking at the next horizon of how to remain relevant. That’s what an MBA is supposed to do, and they do that; you don’t have to go to the 19th century to do that.”

There’s the elemental matter of the weaponry itself. “We even have spears on our buses,” Frank said. “The Seminoles never fought with spears. There were rifles. . . . But tomahawks, that’s more the invention of 19th-century romantic writers. They may have had knives, they may have had all sorts of other weapons, but tomahawks . . .”

For decades, Bowden’s Florida State brought the proper noun “Seminole” into national synonymity with victory. Said Frank, “All people have ideas about themselves, and Florida State plays into the same ideas that the tribe has, kind of their mega-history.” As James E. Billie, chairman of the Tribal Council, said to CNN last January, “Anybody coming here into Florida trying to tell us to change the name, they better go someplace else, because we’re not changing the name.”

“Even though we have a lengthy history of fighting the U.S. government and hiding out in the Everglades to survive, in my lifetime we have never been mistreated or experienced any prejudices from other cultures,” Gopher wrote in an e-mail. “But I know other Native tribes have experienced these difficulties, and may still be experiencing them, so I try to see it from their point of view. And that’s why they are so insulted. But on the other hand, I think to myself, We don’t go around telling them how to live their lives, so why are they concerned with our business?”

Studying Seminoles

“We are still the unconquered Seminoles,” concludes a film at the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Seminole Indian Museum at Big Cypress. “Clearly, they were well under 500 by the end of the 1800s,” Frank said.

Just off the Tamiani Trail and up the quiet two-lane road, they’re a picture of small-town orderliness. There’s a tidy rodeo ground on the left going into the reservation with the tribal logo and “In God We Trust,” a sign noting improvements underway to the Josie Billie Highway, a Seminole Country gift shop, a preschool here, a senior center there. They have Halloween gatherings and Thanksgiving blessings. A statue in front of a gym honors Herman L. Osceola, a U.S. Marine who died in 1984 in a bad-weather helicopter crash in South Korea.

In sculpture, he carries a machine gun.

Florida State fandom doesn’t flood the town. On the outside, even on a game day, you might see only one Florida State banner upon one house all afternoon, even if one tribal leader does have an in-house mural featuring a Seminole holding a dead Gator (University of Florida mascot) and a dead Ibis (University of Miami mascot). It’s Florida, so it has its share of Gator and Hurricane backers. But it’s a Florida town as a routine subject of lecture and prompted discussion 400 miles north-northwest, near where Seminole ancestors used to hunt.

“I like history, and it was a course about Florida, so I was excited to learn more about the history of Florida,” said Bryan Stork, a Florida State graduate in sociology and current New England Patriots starting center. “I kind of already knew about the Seminole tribe because I had read a few books that were based on true stories, but it was just neat to learn their ways and the way they think.”

Joseph Corace, a 2012 graduate from Coral Springs, Fla., who worked as an intern at the museum, said the course surprised him by widening his enthusiasm for history, which mostly had centered on the other side of the world. “You really can see how a network of people can bond together and form and get these types of ties from just being pushed around or encroached upon by war or the advancement of white settlers,” he said.

As the Tuesday morning nears its 10:45 mark, Frank shows a map — either Choctaw or Cherokee, can’t be sure — from 1721. Circles denote various tribes across the Southeast where “friends of friends of friends of friends eventually become friends of friends.” He notes that English or U.S. diplomats would grow confused about with whom to make a treaty. “It’s all fluid,” he says almost 300 years later, to the “Seminoles” studying the Seminoles.